Why keep power lines in harm's way?

Storms always renew the debate about overhead vs. underground distribution of electricity and has many people asking a simple question: Why keep power lines in harm's way?

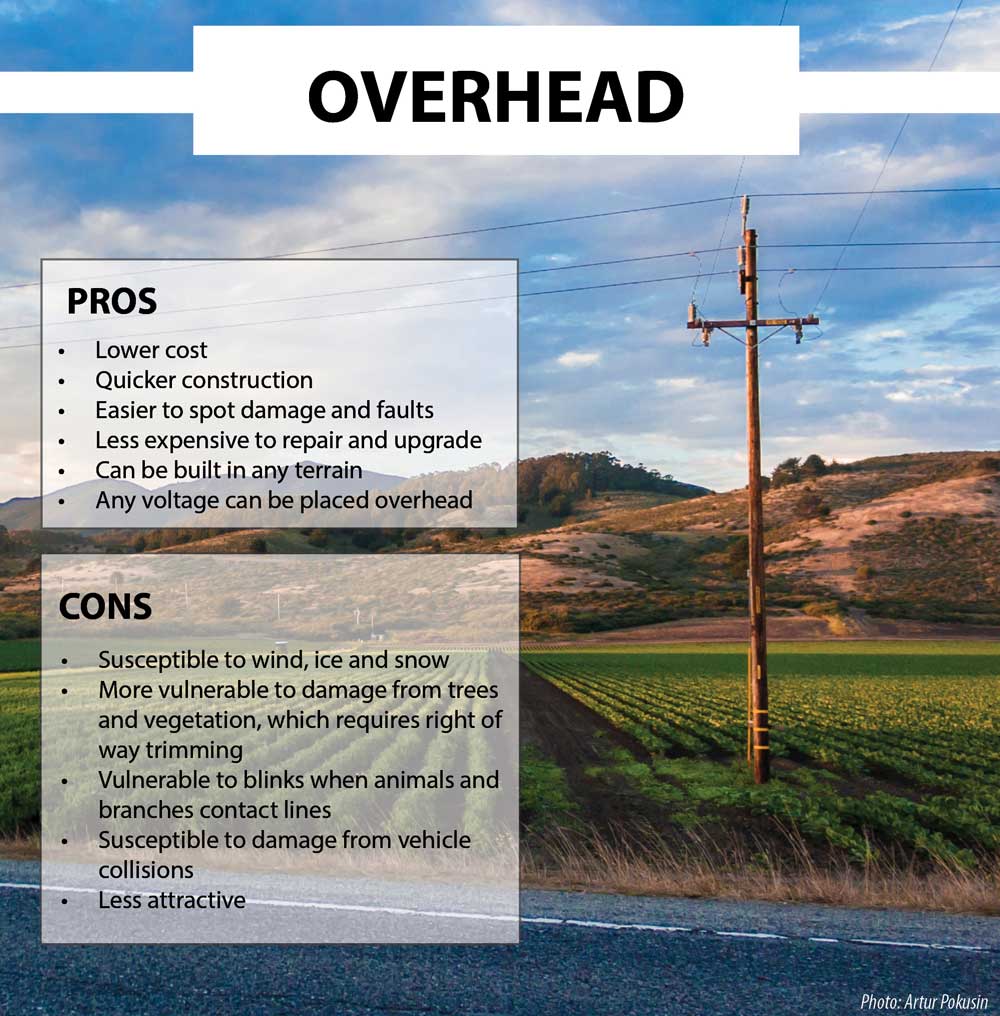

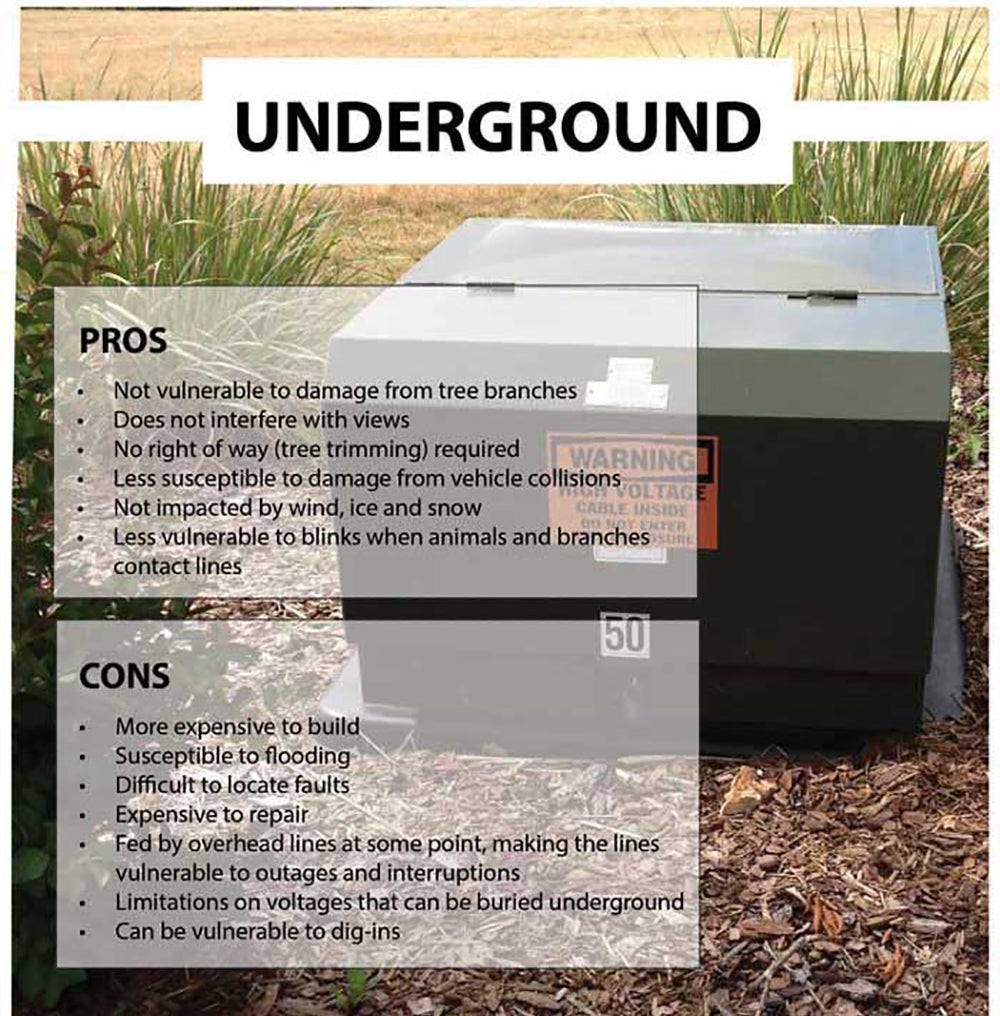

Electricity can be delivered two ways: through overhead or underground power lines. Underground lines may seem advantageous during storms because the lines are not exposed to extreme weather, but the technology doesn't always make sense for co-ops focused on reliability and affordability.

In Rock Energy Cooperative's service area, building three-phase distribution underground lines would cost three to seven times more than overhead lines. Transmission lines could cost as much as 10 times more.

Most underground lines are found in subdivisions where developers request and pay for the option for aesthetic reasons or to comply with local statutes. A high concentration of homes in these areas helps spread out the expense.

But the bulk of Rock Energy's power is delivered via overhead lines in rural areas. About 70 percent of the co-op's 1,265 miles of distribution line are overhead, which helps keep electricity both reliable and affordable for members. The co-op works year-round to minimize and prevent outages caused by trees toppling power lines during storms, said Denny Schultz, director of utility operations at Rock Energy.

"Overhead lines are inspected regularly, and our tree crews work hard to clear branches away from power lines so they hopefully won't cause problems during a storm," Schultz said. "We can't control the weather, but we do everything we can to minimize the damage it causes to our lines."

Faults in underground power lines are not easy to track down and fix. A North Carolina reliability study, which measured both the frequency and duration of power outages, found that underground systems have 50 percent fewer outages than overhead systems, but the average duration of an underground outage was 58 percent longer.

"If a tree falls on an overhead line, you can normally drive down the line, see the problem, and get to work restoring power," Schultz said. "The same holds true for repairing broken insulators and crossarms. If you see it, you can fix it. But underground lines are tough to troubleshoot. You can't find the problem with your eyes. You have to search harder for it, using expensive equipment to track it down based on where the power flow stops. Then a line crew has to dig a hole to reach the spot before repairs can be made."

Long-term reliability is also an issue. As underground lines get older, they become less reliable and are more difficult and costly to repair. A Maryland utility found that customers served by 40-year-old overhead lines had better reliability than those served by 20-year-old underground lines.

Schultz agreed, saying that some of the co-op's overhead lines that were installed 40 and 50 years ago are still providing reliable service to members.